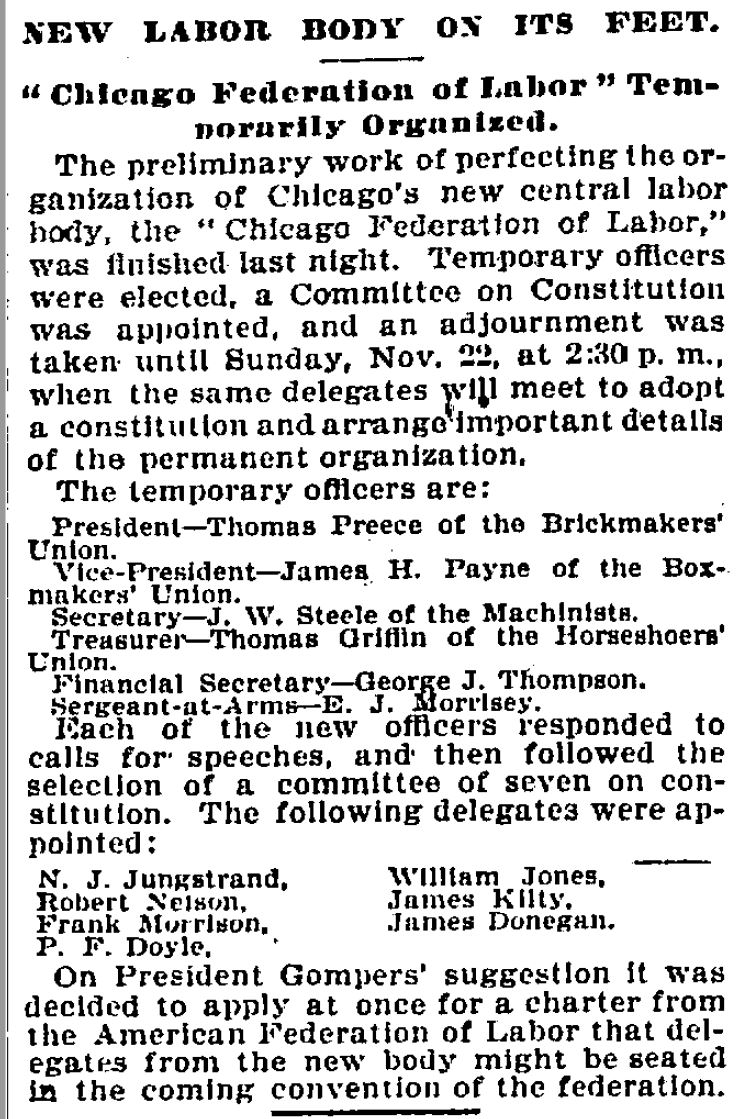

First organized as the General Trades Assembly in 1864 and later the Trades Council and Trades and Labor Assembly, the Chicago Federation of Labor received its charter from the American Federation of Labor on November 9, 1896.

From the Haymarket Affair in 1886 spurred by the fight for the eight-hour day, to the Pullman railroad strike in 1894 over corporate greed and poverty, to the Memorial Day Massacre during the “Little Steel” strikes in 1937, Chicago’s rich labor history stems back to the formative years of our nation’s economy and the modern labor movement.

Today, Chicago’s union members continue to be students of history and the struggles of the men and women who fought for fairness, justice and equality at work.

Late 19th Century

Chicago was the epicenter of organizing in the late 19th century. Immigrants from around the world settled in the city, drawn by its thriving meatpacking industry and critical location in the center of the country. As workers flooded into Chicago, nascent worker organizing efforts sprouted up to fight for decent wages, worker protections, and better working conditions.

In the late 1880s, the main fight was over the eight-hour workday. At the time, workers would be expected to work 10- or 12-hour shifts, six days a week or more. Organizers began demanding an eight-hour workday to provide more rest for workers, as well as more jobs for the unemployed.

In 1886, a general strike was called for May 1 in an effort to enact the eight-hour day. Hundreds of thousands of workers walked off the job, including tens of thousands of Chicagoans. On May 3, locked out strikers at the McCormick Reaper plant in Chicago clashed with strikebreakers and police officers, and two workers were killed.

The next day, May 4, a rally was called to support the McCormick workers in Haymarket Square. There, a peaceful rally included speakers demanding an eight-hour workday. As police closed in on the crowd at the end of the rally, someone threw an explosive device into the fray, triggering a chaos that would leave seven officers dead and dozens of bystanders wounded. Though no one would ever know who threw the bomb, eight anarchist organizers were convicted in a sham trial, and eventually four were executed by the state.

Later, in 1894, Chicago again emerged as the focal point of union activism, as workers went on strike protesting wage cuts at the Pullman Palace Car Company, triggering a nationwide railroad strike. Company owner George Pullman slashed workers’ wages in response to severe recession, but refused to lower rents in the Pullman company town. Members of the American Railway Union went on strike in Chicago and nationwide, bringing nationwide rail transit to a halt. Eventually, the strike was violently broken by the Federal government, though President Grover Cleveland did designate the first Monday in September to be Labor Day, a holiday still celebrated today.

It is in this atmosphere of labor activism and worker oppression that the Chicago Federation of Labor was born. Labor leaders recognized that their voices were more powerful together as one, as opposed to fractured into individual unions. The CFL’s first president was Thomas Preece, a bricklayer, and the Federation would eventually have nine men serve as president in its first decade of existence.

John Fitzpatrick

In 1906, Irish immigrant and President of Horseshoers Local 4 John J. Fitzpatrick was elected president of the CFL. Fitzpatrick was an organizer and a committed unionist who railed against corruption and cronyism that befell many other labor organizations. Fitzpatrick served as president for a year in 1900, but his second tenure, which started in January 1906, would last until his death in 1946.

President Fitzpatrick moved the CFL forward in innumerable ways. He created the weekly news publications, the New Majority, the predecessor to the Federation News, in 1919 as a vehicle for delivering news to workers without relying on the unsympathetic press. He created a Labor Party and ran for Mayor of Chicago and U.S. Senator, bringing labor into the political conversation as a means to improve workers rights. Along with Secretary-Treasurer Edward Nockels, the CFL created WCFL in 1926, the Voice of Labor.

John Fitzpatrick, Chicago Federation of Labor President

Fitzpatrick and Nockels advanced the mission of the CFL to fight for racial, social, and economic justice. The CFL focused on organizing the steel mills and stock yards that chewed through workers, especially immigrants and workers of color. In organizing steelworkers, Fitzpatrick said,” I don’t care what the by-laws of the international unions are, if they keep the Negro out, they have got to be changed to let him in.” During the “Red Summer” of 1919 as race riots engulfed Chicago, the New Majority called for white union members to stand with Black workers, writing:

“A heavy responsibility rests on the white portion of the community to stop assaults on negroes by white men…All of the influence of the unions should be exerted on the community to protect colored fellow workers from the unreasoning frenzy of racial prejudice.”

Later that same year, Fitzpatrick and his dear friend Mary G. Harris “Mother” Jones led the steel strike of 1919, shutting down steel plants in Pennsylvania, Chicago, and across the country. Fitzpatrick’s CFL also supported the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, founded by A. Philip Randolph, the first union in the nation with African American leadership.

Fitzpatrick headed the CFL for four decades, navigating two World Wars and the Great Depression, as well as countless strikes and rallies, perhaps most notably the Little Steel Strike and Memorial Day Massacre of 1937. Fitzgerald passed away Sept. 27, 1946, at his home in Chicago. Upon his death, the CFL passed a resolution honoring its longtime president, saying:

“The Chicago Federation of Labor hereby tender its highest regards, love and esteem to the memory of one who was with us so long, and who labored so strenuously wand unselfishly through the years for the benefits of him who ‘earns his bread by the sweat of his brow.’ May that memory of him be always cherished by us, and may we continue to promote and foster his ideals.”

The CFL Under William A. Lee

Upon Fitzpatrick’s death, William A. Lee, President of Bakery Drivers Union Local 734 and Vice President of the CFL, was elected president, and he would go one to serve for nearly 40 years. Lee continued Fitzpatrick’s commitment to racial and social justice through trade unionism. Lee’s close political and personal ties to City Hall also allowed union workers to make significant gains through political and legislative action.

In 1962, Lee presided over the merger of the Chicago Federation of Labor with the Cook County Industrial Union Council, South Chicago Trades and Labor Assembly, and Calumet Joint Labor Council at Plumbers Hall on Jan. 8, 1962. Of the merger, Lee said, “We’re proud of our separate records…think of how much more we’ll do together.”

In 1964 and 1966, the CFL and other labor organizations supported Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in his visits to and rallies in Chicago as he fought for equal rights for all. Lee celebrated the signing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act on the front page of the Federation News, writing, “[w]e have come closer to the ideal of the Declaration of Independence with the Civil Rights Law.” WCFL aired programming supporting the Civil Rights movement urging workers to stand with those fighting for equality.

Upon Dr. King’s death in 1968, Lee recommitted the CFL to King’s work, saying “Labor will join all others of good will to take up the burden and the challenge he has left us…to eliminate all poverty, blight and discrimination.”

Under Lee’s leadership, the CFL strove to make practical advances in the lives of workers in Chicago and beyond. Writing in the 75th anniversary edition of the Federation News in 1971, Lee expounded on this philosophy, writing:

“In the same spirit of practical idealism, which actually means concern for the well-being of others, we go beyond merely advocating. We are interested in improving the equality of life. We have always been deeply involved in very type of community project…health and welfare agencies, improvement of parks and playgrounds, slum clearance and public housing, a clean environment and equality of all people.”

Lee passed away on June 16, 1984, at the age of 89, ending a nearly 80-year run for the CFL under just two presidents. Lee was remembered as a master negotiator who preferred to negotiate peaceful settlements rather than revert to confrontation.

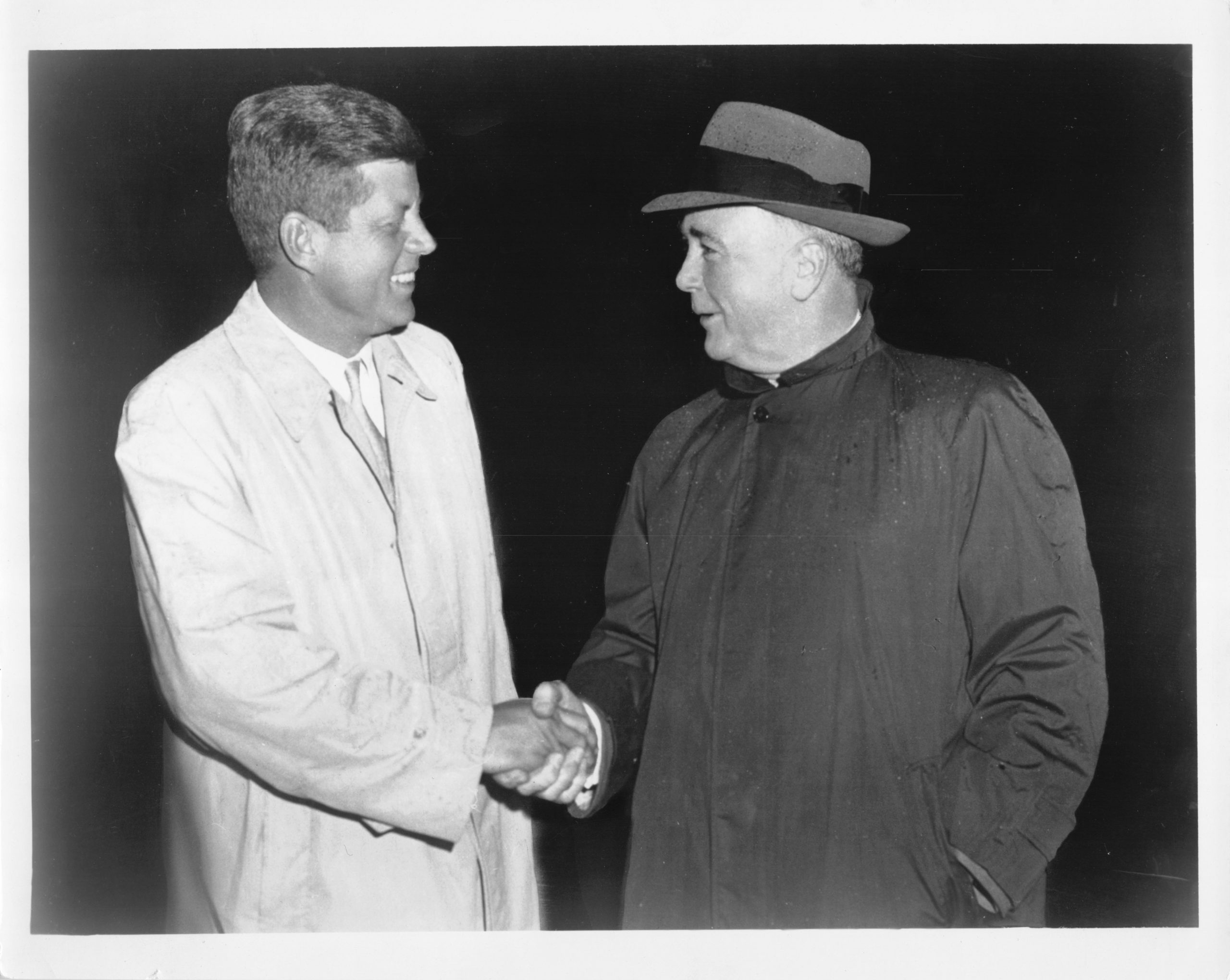

CFL President William A. Lee (right) meets President John F. Kennedy in 1962.

Fighting for Workers in the Modern Era

In the 1980s, a key battleground for the CFL was the 25-year fight to expand collective bargaining rights to public employees in the city of Chicago. The 1983 mayoral election pivoted around the issue for the CFL. Incumbent Jane Byrne was endorsed by the federation in the primary, though she would lose to U.S. Rep. Harold Washington. In the general election, the CFL unanimously endorsed Washington, helping him secure victory in a bitter and racially-charged campaign. Later in 1983, the Illinois General Assembly passed the Public Employees Bargaining Act with Mayor Washington leading the charge. The CFL would go on to endorse Washington for re-election in 1987.

Throughout recent decades, the CFL has continued the fight for economic, social, and racial justice. Under President Robert Healey, the CFL held a rally with Cesar Chavez in support of California farmworkers in 1990. In 1993, the CFL supported the Illinois Labor Network Against Apartheid as it hosted Nelson Mandela at Plumbers’ Hall in Chicago. In 1994 under the leadership of President Don Turner, the CFL launched its Workers’ Assistance Committee, now the CFL Workforce and Community Initiative, with the goal of helping union members who lost their jobs due to closings or layoffs. Today, the Workforce and Community Initiative runs a variety of job training and workforce development programs helping workers across the region.

President Dennis Gannon continued the CFL’s important role in civic and political affairs. He helped guide CFL in its central role during in the 1996 Democratic convention and organized a presidential forum of candidates in 2007, helping boost then-Sen. Barack Obama’s nascent campaign. Under Gannon, city workers ratified a 10-year contract in the run up to Chicago’s Olympic bid and the state passed a massive state capital bill in 2009.

Under President Jorge Ramirez, the CFL played a central role in the fight against a rising tide of anti-unionism that swept the nation and the state. In 2011, President Ramirez led the fight against pension cuts through massive rallies with the We Are One coalition and in support of Wisconsin workers fighting far-right Gov. Scott Walker. President Ramirez’s work earned him a seat on the AFL-CIO Executive Council, demonstrating Chicago’s continued importance to the national labor movement.

Today, the CFL continues to embody the ethos of practical idealism and unrelenting determination for working people that has sustained the organization for 125 years. Rarely does a major event, initiative, campaign, or project in Chicago or Cook County succeed without the CFL’s support and involvement. Under President Robert G. Reiter, Jr., the CFL added organizing capacity, won new rights for Chicago workers, and helped working people navigate a once-in-a-generation pandemic.

The spirit of 1896, bringing workers together as one to fight for dignity and rights on the job, is alive and well in the CFL today.