As she glanced at the TV screen, a wave of shock shot through Katie Jordan’s body like a lightning bolt. Then came bewilderment. Then fear. She had only been in the country a short while, and now her face was all over Soviet state-run TV.

“The anchor on the TV said, ‘Where is that woman from America?’ I got leery and wondered, ‘Why are they looking for me now?’” Jordan said.

What came next was a sigh of relief for the former teen model-turned tailor-turned union activist from Hot Springs, Arkansas. She had a long history of speaking her mind and standing up for what’s right. She just assumed the target placed on her back countless other times had followed her overseas.

She was already suspicious of one member of her group of Americans visiting Moscow. In the evenings, he would slip away with different excuses for why he had to step out. Other guests were highly restricted on where they could and could not go. Jordan would later learn that man was attending meetings with Communist Party officials, and he was a member of the American Communist Party.

However, it turned out Jordan was not caught up in a Cold War action movie come to life herself.

“The guide who was accompanying us then said, ‘No, no Katie. They just want to get to know you, you, see?’ It was still such a shock,” Jordan said.

Jordan was welcomed in Moscow as if she was a celebrity. She was part of a delegation invited to visit Moscow in the mid-1980s to meet with Soviet leaders. She was selected specifically because of her labor activism with Amalgamated Clothing Workers Local 5. She did not expect the thawing out of Cold War hostilities.

Her days were filled with meetings, tours and experiencing a country that had been off-limits to Americans for decades. After a while, she got to see how two cultures were different, but the people were the same. Jordan saw that whether it was capitalism or communism, workers still faced struggle every day from a class trying to control them.

“In Russia back then, all the apartments for workers were free. They did not pay anything. But they were assigned to people, and they gave you only as many rooms as you needed, no exceptions. If someone wanted to stay the night, or host a large gathering, you could not do that,” Jordan said.

Before her visit was finished, Jordan would be asked by Soviet leaders to deliver a speech at their conference.

“I got up and I told them I’m for workers everywhere, all around the world. That’s me. We’re all human beings and we all deserve to live in dignity. Then I wound up on TV again and people were saying, ‘Did you see that woman from America on TV again?’” Jordan said.

Speaking Up

Her trip to Russia, was one of many Katie Jordan has embarked on over her 60-plus year career preaching her own brand of social justice, solidarity, and self-respect. In her seven decades-and counting in the labor movement, she has been from coast-to-coast and trotted the globe. She has met foreign dignitaries and world leaders. She has been decorated with countless awards and honors. But you would not be able to guess that by looking at the sharply dressed woman sitting in the front row of monthly delegates meetings of the Chicago Federation of Labor.

“Katie’s spirit is indomitable. Someone her age, you may expect to be a fly on the wall at events and functions. Not Katie,” said Chicago Federation Labor President Bob Reiter. “She is an adventurous person by nature, unafraid of anything. If you check the minutes of CFL Delegate meetings over the last 50 years, I bet you will see Katie Jordan’s name all over them!”

Jordan rose from her seat to speak during the most recent meeting in February. This time, it was only to set the record straight. She had been described in previous meeting minutes as a “CBTU member.”

“I’m not just a member of CBTU,” Jordan told the roomful of CFL Delegates, most at least fifty years her junior. “I’m a member of CLUW too, don’t forget that.”

Jordan has long been a proud member of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists since their formation in 1972. She was also a founding member of the first chapter of the Coalition for Labor Union Women in 1974. Both organizations were founded in Chicago. Both organizations are central to Katie Jordan’s identity as a labor activist.

But she would not tag herself with any labels like that. In fact, Katie Jordan did not even know she was a part of the labor movement until after she became one of the strongest voices for working people in Chicago. She learned the lessons of fairness, persistence, and solidarity as a young girl growing up in the Jim Crow South. To this day, the true guiding force in Jordan’s life was her moral compass.

No Fear of Needles

Jordan was born in a town “too small to even put on the map” in rural Arkansas in 1928. There were few opportunities in that region back then, especially for Black people, so her family moved to the city of Hot Springs when she was a teenager.

Jordan remembers her mother as a talented tailor and seamstress. Her mother made all their clothes by hand. Jordan would spend hours quietly watching her mother work while the other children played outside. She paid attention to every stitch and seam.

“Everything she did, I watched my mom. She would quilt and embroider, and give me a stool, and I would sit there with my arms folded and watch. I would sit on a stool and just watch. Then eventually she would show me how,” Jordan said.

This launched her lifelong fascination with fashion and needlework. She learned more and more from her mother and wanted to keep learning more techniques and tools. She longed to try her mother’s sewing machine, but that was off limits. It was one of her mother’s most prized possessions. But Jordan did not like to be told she could not do something.

One day, when her mother came home with fabric to make Easter dresses for everyone, Jordan did not like the pattern her mother had picked out. Because she had watched her mother sewing and stitching, Jordan finally had confidence enough to make a dress for herself.

“I wanted to try that machine so bad. I knew my mother was going to be gone one day. So, I picked out material on my own and I said, ‘You can do this! But you’ve got to get it done before your mother comes home,’” Jordan said.

She finished in time, then hung the dress on the back of her bedroom door to set up a reveal for her mother when she got home. Jordan quivered with fear of the wrath she would encounter for disobeying her mother. The moment of truth was about to arrive.

“So, my mom picked up the dress and I said, “Look what I did.’ And she looked at the dress, she held it up and looked at the seams, and she said, ‘You did this?… This is pretty good!’ And it was like I had lost a 100-pound weight. I was so relieved. Shortly after that, I started making designs and dresses for all my friends and family,” Jordan said.

Jordan would eventually set up a shop in her own home and become the premier dressmaker in Hot Springs. She recalls being the go-to tailor for all the young women in town. Ready for the next challenge, Jordan took modeling classes and began to model her own work. That led to the most exclusive stores in town asking Jordan to model their clothes. And because she was offered the stores’ clothes at a discount, she was often the best dressed woman in Hot Springs.

Jordan modeled, made clothes, and worked in Hot Springs’ famous bathhouses for several years. She also married and started a family. But something inside her told her it was time to move. It was the 1960s. The American landscape was changing. Katie Jordan would leave Arkansas in search of something more.

“Eenie, Meenie, Minie, Moe, It Has to Be Chicago”

Katie Jordan had never been to Chicago. She had only heard fascinating stories from family and friends about the city, full of excitement and opportunity. She had recently become a single mother of three children. She only had six cents to her name, but she was ready for another adventure.

“I remember thinking about it one night about what I was going to do next, and just said to myself, ‘Eenie, meenie, minie, moe, it has to be Chicago!’” Jordan said.

Jordan decided to remarry before moving to Chicago, but that relationship quickly went south.

“My mom always said, you don’t have to allow people to disrespect you. They will only do that if you allow it. And I thought I was being terribly disrespected by this guy I had just married. And after three weeks, it was over. I was a single mom. And in Chicago, where I didn’t know were anybody or anything was.”

Jordan found help finding her way in Chicago from an old classmate from Hot Springs, who strangely enough, settled a block away from where Jordan had settled in Chicago. Jordan then visited the unemployment office on State Street in the Loop to find a job prior to the busy holiday season.

Jordan was not looking for a permanent job. She was looking for something that would allow her to make a little money in order to buy Christmas gifts for her family. She told the unemployment office she wanted any job they had available in the fashion industry. Her dream was to be a designer. They told her they did not have anything in fashion. They said something that involved clothing was available just across the street and she could start tomorrow.

Jordan realized she was in a brand-new world on her first day on the job at the Henry C. Lytton Clothing Co. She took her lunch break along with the rest of the women working on her floor. She noticed a woman making a sandwich and a cup of coffee. She made the sandwich, cut it in two, and wrapped up half of it. Then she saw a man walk in, sit down, ate the half-sandwich left, drank the coffee, and left.

“I found out that it was her husband. It was funny to me. I said to her, ‘Really? Even at work, you have to make his sandwich and fix his coffee?’ I wasn’t brought up that way,” Jordan said.

It did not take long for Jordan to spot other things that seemed out of place at Lytton. She naturally became the watchdog for her coworkers. She spoke up for her coworkers who were being unfairly relegated to part-time worker status. She pushed for more training for more workers on different sewing machines, something that previously bottlenecked production.

“Every time you turned around, it seems like they were doing something that was awry,” Jordan said.

“I’ll just stay on a bit longer”

When Jordan completed her first two weeks at Lytton’s, she received her paycheck. The amount listed on the check was incorrect. Fraught, she went right to her supervisor. Her supervisor affirmed the check was correct. Jordan said it was not correct. Her supervisor got on the phone with payroll, reaffirming the check was correct. Jordan stood pat. She called payroll again; they held firm too. So, Jordan went up to payroll to show them the error.

“My mom always said, ‘Always know what your pay is supposed to be. Know what they owe you. Don’t wait and accept what they give you and figure they’ll do the right thing,’” Jordan said.

Jordan found out her check was short due to an accounting error. Apparently, the company was paying her bi-monthly, but the amounts on her check reflected two weeks of work. Payroll told her they would fix the error and pay her what she is owed on her next check. She went back downstairs and told her coworkers what had happened.

“No mind you, I only went up there to talk about my paycheck, but when I got back downstairs, everybody started pulling out their paychecks. I would look at them and say, ‘That’s wrong… that’s wrong… yours is wrong’” Jordan said. “I told them they owe you that money, just like they owe me.”

Receipts in hand, Katie marched back to payroll and made her case to the company. She even got the labor board involved. She was able to win a year’s worth of backpay for all her coworkers.

“There were so many women I worked with that didn’t speak English or had some other situation. They needed help. So, I kept saying to myself, ‘I’ll stay on a little longer.’ And I did, for twenty more years!” Jordan said.

The “Katie Clause”

Lytton had a men’s and women’s department that worked independently of each other. There were men and women who worked in the men’s department, but the women’s department was only women. The men’s clothing workers were union, but the women’s clothing workers were not.

This scenario was not totally uncommon back in those days. Until 1980, the median income for women was 60% of what it was for men. The growing feminist movement was just beginning to galvanize and break glass ceilings all across America.

One day while Jordan was working, representatives from the Amalgamated Clothing Workers walked in to visit the men’s workers. Jordan and the rep began talking, and he told Jordan the women from the women’s department should join their union. Jordan spoke to her department, and everyone overwhelmingly agreed to go union. The process was surprisingly smooth for one simple reason.

“I had been there a while now, so they knew not to mess with Katie Jordan,” Jordan said.

Her shop joined the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers on March 1, 1966. When it came time to elect a shop steward, Jordan was elected steward not just for the women’s department, but the men’s department too.

Jordan’s duties as a shop steward came natural to her. In fact, nearly all of the strong ideals and characteristics associated with solidarity and unionism, Jordan had learned from her mother and the church while growing up. It was second nature.

One challenge of leading a brand-new unit that had never been in a union before was educating her coworkers about their rights in the workplace. This task was made increasingly difficult by the fact that a lot of Jordan’s coworkers spoke little or no English at all. Jordan, of course, had an answer for that.

“Most of these women had never seen a contract before, let alone knew what it meant. But I knew they all had sons and daughter that al spoke pretty good English. I would write on each contract and say, ‘Take this home. This is my phone number. Tell your children to call me.’ And so, I would sit on the phone every night with our members and make sure they understood their rights and exactly what was in the contract.

One day at Lytton, Jordan noticed a pileup of coats in her department, stifling production. She investigated and found out the woman whose job it was to run the machine responsible for finishing coats was on vacation. The machine was not incredibly complex to operate but did require minimal training. She asked again, and again why more people were not trained on this machine, until she finally told her supervisor she would run the machine.

The tactic of not training employees in different jobs at the same workplace has long been a tactic to keep workers docile and complacent. Lytton’s was no different. Only they were not just trying to keep wages low, they were keeping women and black workers from being promoted within the company to higher positions.

Jordan began to notice that when an advisor or tailor-fitter would retire, the two most well-paying, prestigious, and white male dominated jobs at the shop, the company usually brought in an outside hire to fill the vacant positions. Jordan raised the issue to management and fought to establish an internal training program at Lytton’s.

“Most tailors and lower jobs were done by women, so this gave the women a chance to move up and make more money at one of the higher positions like advisor and tailor-fitter,” Jordan said.

And like any good union steward, she did not settle for management’s word. From then on, the union’s contract with Lytton’s contained a clause the members called a “Katie clause” that called for on-the-job-training for employees for promotions before any outside hiring could be implemented, giving women and people of color an opportunity for promotions. Jordan became the first woman to serve on the negotiating committee at Lytton’s and would serve on every negotiating committee until the company went out of business in the 1980s.

Follow Before You Lead

The biggest influence in Jordan’s life was her own mother. She learned most of her core values from her mother, including self-respect and self-love–the latter leading to the development of her incredible self-confidence, and her lifelong fondness for fashion.

“My mother always taught us, when you go out any place to meet people, always dress presentable and always love how you look. You don’t have to be ashamed of your body. It’s important to always look in the mirror and tell yourself, ‘I look great!’” Jordan said.

By 1970, a little over four years after she started as a tailor at Henry C, Lytton Clothing Co., she had been appointed to serve on the Executive Board of her local union. Just a few years later, she would be elected the first woman and African American president of her local union. Once she reached the upper levels of union leadership, there were reminders everywhere of the ongoing fight for equality.

“I remember attending a union meeting, and they served us lunch. Almost all the union folks were men. All the servers were women. We need to change that,” Jordan said.

Through her time in the Black labor movement, Jordan had met and befriended other leaders that would help guide her on her crusade for change. Charlie Hayes and Bill Lucy founded the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists in Chicago in 1972. Jordan naturally became involved with CBTU, and credits Hayes and Lucy as invaluable mentors during in her life. However, roughly 40 percent of the 1,200 delegates who attended the first CBTU conference were Black women. One of those women was Addie Wyatt, the trailblazing minister and the first Black woman president of the United Packinghouse Workers of America.

“I first met Wyatt when I got involved with CLUW. After they’d formed, I became a founding member of the first chapter ever established for CLUW,” Jordan said. “Addie Wyatt was a powerful mentor for me.”

The two women had a lot in common. Both were born in the South and moved to Chicago with their families in search of opportunity. Both broke glass ceilings by ascending to the highest leadership positions within their unions. And both developed empathy and a strong sense of responsibility from their mothers.

“I learned everything I know about good listening skills from Addie Wyatt. She taught me what kind of attitude a leader should have. She said, ‘If you cannot follow, you cannot lead,’ and that really stuck with me,” Jordan said.

Jordan took that advice to heart and has been listening and learning all over the world ever since. She has attended countless leadership and labor education programs over the years and taught a few courses herself. Jordan was a longtime teaching fellow at the Regina V. Polk Women’s Labor Leadership Program and organized an annual Women’s History Month program with Illinois AFL-CIO President Margaret Blackshere–the organization’s first woman president. Jordan has influenced multiple generations of labor leaders through the years.

Marching Together, Moving Forward

In 1992 Katie Jordan was named the Chicago Federation of Labor’s Woman of the Year. At the time, she was the president of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Local 5 and honored for her nearly three decades of work in the labor movement.

“One voice can awaken the world. One voice can sing the note. But it is only by marching together that we can move forward. One hand clapping can’t set the beat alone, but one hand clasped with another can lead a marching band. By joining together in solidarity, we can change the world,” Jordan told Federation News in 1992.

Over 30 years since receiving that award, Jordan has been and plans to remain as active as ever. She retired officially as a fitter-tailor in 1995 but never as a union member. In Jordan’s eyes, you never really retire as a union member as long as there are injustices to fight and wrongs to be righted.

Changing the world for the better has been Katie Jordan’s mission since she knew right from wrong. As a member of two historically discriminated against groups, Jordan has faced her uphill climb in this world with no fear. She smashed glass ceilings and held open the door for countless other women and people of color over the years.

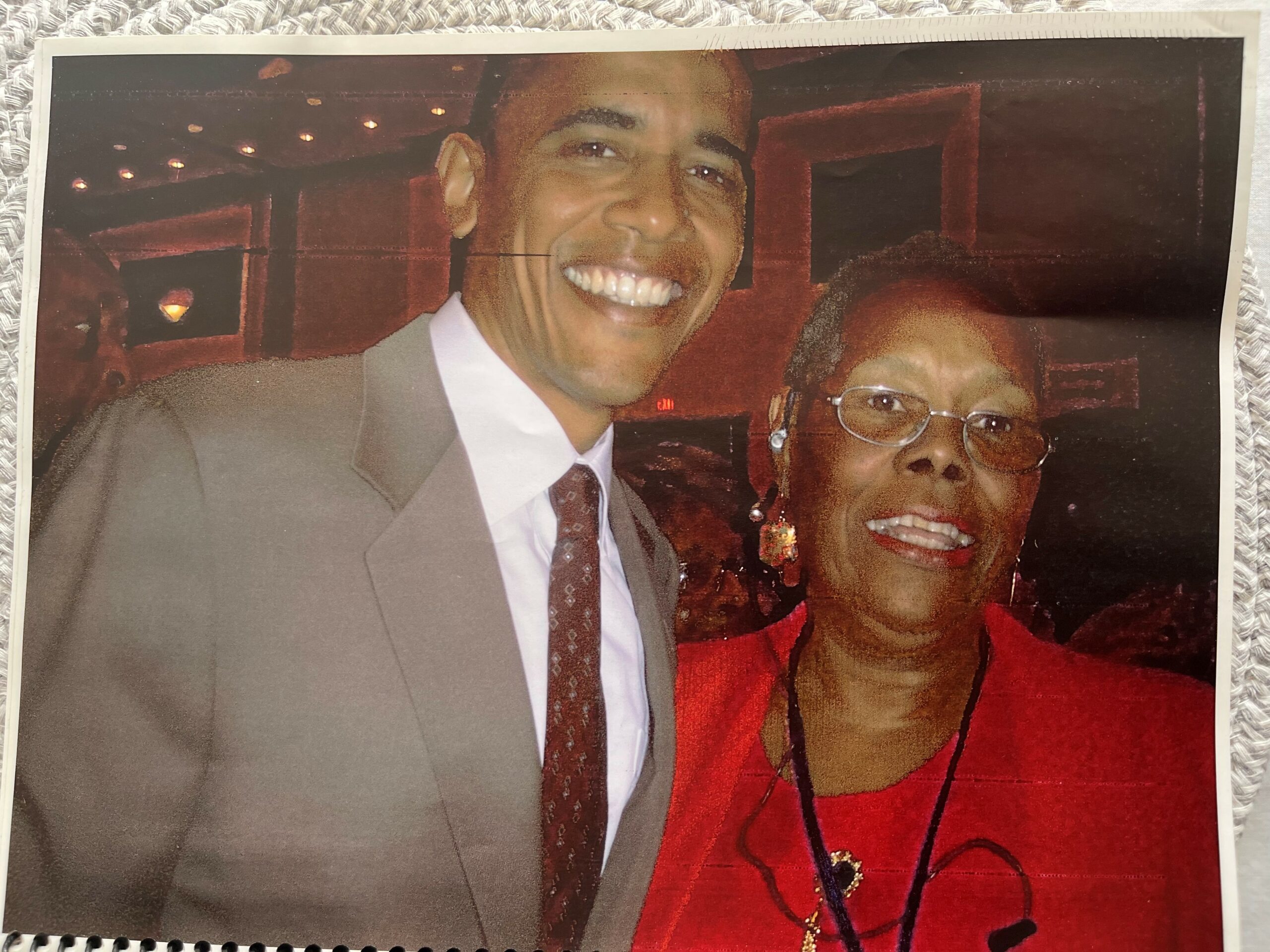

Katie Jordan has been an active union member for over fifty years with the former Amalgamated Clothing Workers, and Workers United. She remains a staple at Chicago Federation of Labor Delegate meetings and serves as Treasurer of the Illinois Alliance of Retired Americans, Trustee of the Illinois Labor History Society, a member of the Policy Council of Citizen Action Illinois and President of Workers United Retirees’ Organization. Throughout her career she’ has held the positions of shop steward, local secretary, vice-president, and president. She has seemingly done it all. Her could be its own museum, decorated with honors, awards and pictures covering nearly every inch. But those photo ops and awards are far from her proudest achievement.

When looking back on her long and storied career, there is one thing that Katie Jordan is most proud of. It also happens to be the thing that keeps her optimistic and focused on building a better future.

“I am most proud of the fact that I have helped uplift many, many others over my time. When I look back, I gave my time to help someone else and helped pull them up to be better. There’s a young man in my ward running for alderman. I’ve been one of his mentors. I’d see him in church and teach him in Sunday school. That’s what keeps me going. The next generation,” Jordan said.

That young man is William A. Hall. He is running for Alderman in Chicago’s 6th Ward and is, of course, endorsed by the Chicago Federation of Labor.

“Ms. Jordan is the G.O.A.T. She embodied the principles of dignity and fighting for what’s right. She was always challenging us kids, and checking how we were doing in school. She taught us to respect each other and to be kind and include others when they were being left out. She is gentle, tender but also strong and steadfast. She is my rock. I would not be where I am today, without the tutelage of Ms. Katie Jordan,” Hall said.