An endless stream of thoughts were running through her head. What she was about to do would almost certainly end in her being arrested. But all Rosetta Daylie, president of AFSCME Council 31, could think about were her commitments– to her brothers and sisters in the labor movement and the cause to end apartheid in South Africa. That, and one other thought.

“I was going crazy because I said, ‘Oh if my mother turns on the television and sees it, she’s going to die,’” Daylie said.

Moments earlier, Daylie had received a call from William Lucy, President of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists. He had a conflict and couldn’t attend the planned sit-in at the South African Consulate in Chicago. She was going to lead the demonstration, knowing full and well she and others would be escorted out in handcuffs.

And after she was eventually arrested and taken to jail, she had an ace up her sleeve.

“I actually represented the civilian workers at 11th & State Police Headquarters, so a lot of my members knew that I was in there. And so, they made sure I had something to eat,” Daylie said.

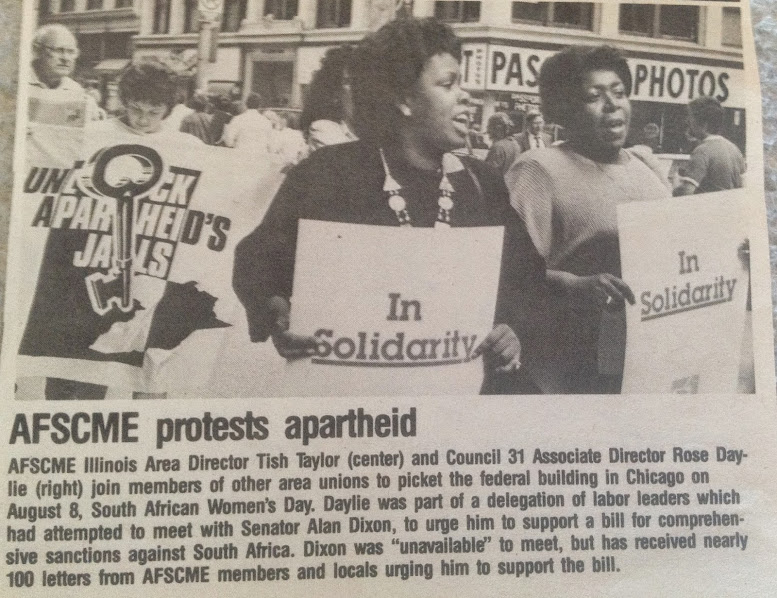

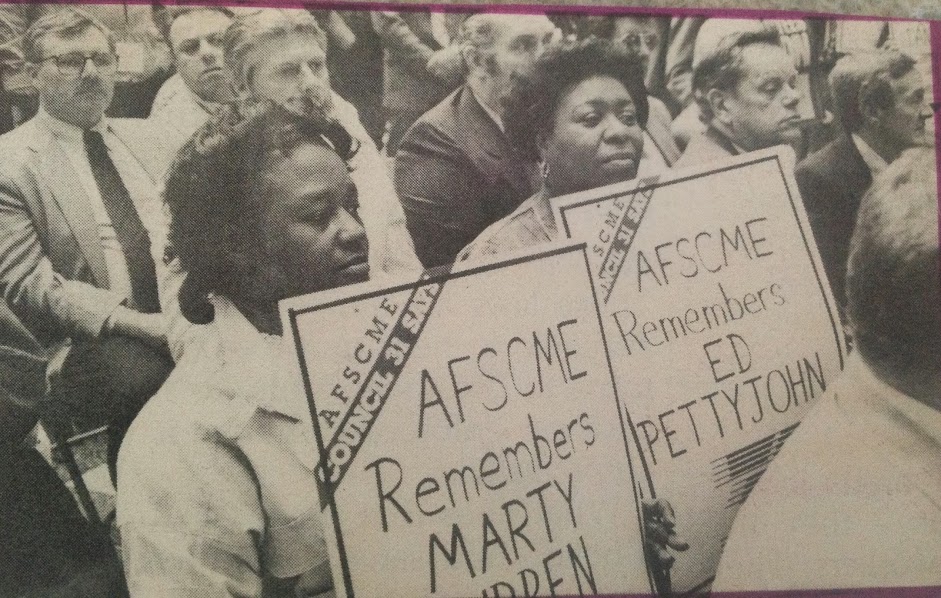

Daylie served as an active member of the Illinois Labor Network Against Apartheid since it formed in 1987. She would lead meetings and rallies, host and lodge South African delegates in her own home, and even spend weeks in South Africa assisting the country’s first free and fair election in 1994 that resulted in Nelson Mandela’s being elected president.

Along with the birth of her four children, she counts her work on the 1994 South African Election as one of the two highlights of her life. The other was the day Harold Washington was elected the first Black Mayor of Chicago.

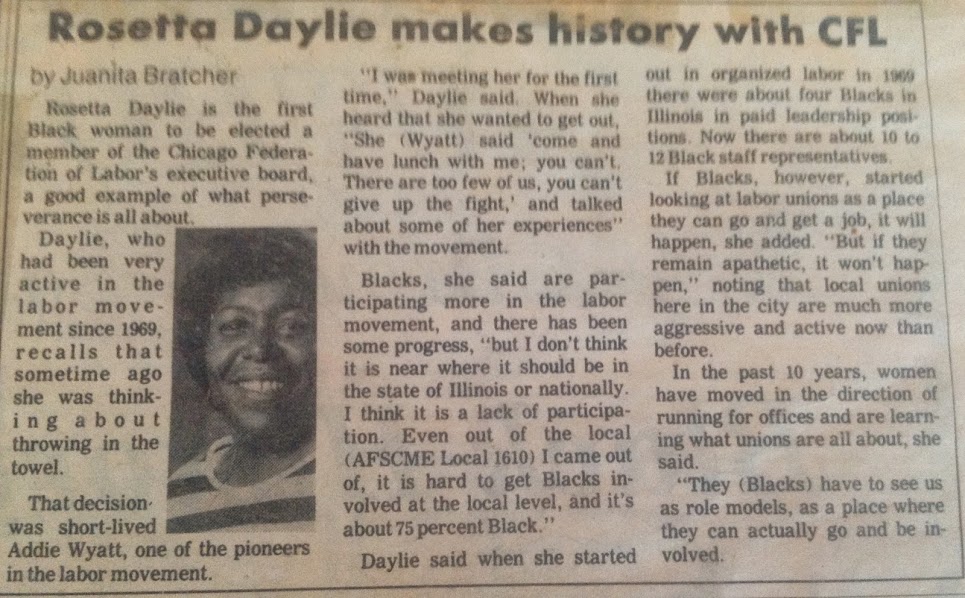

Daylie’s life is full of a few firsts of her own: she was the first Black woman elected to the Executive Board of the Chicago Federation of Labor in 1990 and has been a fixture of the organization for the past 33 years. Her seven decades in the labor movement have been guided by the principles of dignity, respect and justice she learned from the strong women and men in her life, including her formerly enslaved great-great grandmother, who lived to be 102. Daylie believes her mission on this earth is to defend the rights of people whenever and wherever they are threatened–whether it be voting rights, workers’ rights or basic human rights.

Three Churches, One Sunday

Daylie was born on Chicago’s South Side in 1939. Her parents had moved to Chicago from Athens, Ga. during the Great Migration and settled in Washington Park. Daylie recalls a strong sense of community among neighbors growing up but didn’t learn until years later there was a special bond between a lot of them.

“I found out in the last couple of years that actually everyone that came to Chicago from my mom’s hometown lived in that neighborhood,” Daylie said. “And so, it was really like a family. I mean, we never locked our doors. We could just go in and out of each other’s houses. Everybody in the neighborhood knew they could chastise or punish anybody that got out of order, all the children in the neighborhood. So, it was like a small community.”

Daylie grew up in a large multi-family home with her parents, as well as her mother’s sister and brother and their families. She filled her childhood days with skipping rope and playing hopscotch like the other girls in the neighborhood. She would often be called to work in her uncle’s neighborhood grocery store. It was a family-run business. Everyone was expected to pitch in.

“We all worked in the grocery store when we were very young. I can remember my uncle waking us up really early some days and saying, ‘Get up. We have to open the store. Mrs. So-and-so is out of milk.’ And we would get up and open up the store,” Daylie said. “I would sometimes groan and ask why, but that was an early lesson for me about how to treat people.”

Other family activities kept Daylie busy while she was growing up. Her aunt was a precinct captain in her ward, so she became a “good young democrat.” She attended Catholic School, which came with its own Sunday obligations on top of the ones she already had.

“I had to go to mass every Sunday, because that was part of going to Catholic School. When I left there, I’d go to church with my mom & dad. And after that, we had to attend another church service with the whole family. I was always busy on Sundays,” Daylie said.

Saturdays were often busy for Daylie as well. Her mother would go around to each bakery in the neighborhood and take orders for Saturday dinners, then cook and deliver the meals each week. Coincidentally, the job that launched Daylie into a life of labor activism was in food service.

Crash Course: Solidarity

She was incredibly conflicted.

On the first day of her new job in the Dietary Department of Chicago Read Mental Health Center, Daylie encountered a picket line. Nurses were on strike.

It was the mid-1960s and Daylie’s family depended on her income to make ends meet. She needed this job. She had just left her position as a food service worker at a home for the blind because she was egregiously passed up for a promotion to supervisor.

“I walked right into a wildcat strike. I was not involved in any unions back then, didn’t know anything about unions. So, they were hollering at me not to cross the picket line, but I thought to myself, ‘I just left another job I know they’re not going to let me back to,’ so I had to cross,” Daylie said.

Daylie remembers the nurses worked in what today would be called the intensive care unit and held a wildcat strike to demand a pay raise. The nurses who walked out that day were in a union but had no bargaining power. The state had not yet passed the Public Labor Relations Act for public employees.

“We had a union at Read, but we were pretty powerless. We won some stuff, but we didn’t have the legal right to bargain,” Daylie said.

Daylie quickly rose through the ranks of her AFSCME local at Read. She became a steward and later an organizer. One of the first major campaigns she worked on was to push state lawmakers to grant collective bargaining rights to state workers. Because of AFSCME’s efforts, then Illinois Gov. Dan Walker signed an executive order to grant state workers collective bargaining rights in 1973. More than 60,000 state workers would organize in the years that followed.

“Later on, when I was an organizer for AFSCME, I ran into some of those same nurses who went on that wildcat strike. They saw me, and said, ‘Oh I know you won’t be trying to organize us!’ and we laughed about it.”

One would think the mortal sin of crossing a picket line would surely lead to excommunication from the labor community. But Daylie, being a good Catholic, recognized her wrong and repented. She would dedicate her career to fight for justice and workers.

Harold? He’s My Friend

In the late 1960’s, huge layoffs were looming in state government, including droves of AFSCME members. 140 members from Daylie’s home local were slated to lose their jobs.

“There had never been a lay off in civil service in the state of Illinois. There was no such thing. That’s why most African Americans took state jobs because you got vacation, you got sick time and there was never a layoff,” Daylie said.

Daylie, at the time an active rank-and-file member, was selected by her local union’s president to meet with a State Representative to see what, if anything, could be done. The WWII veteran and charming young man who represented Illinois’ 26th district pledged to be a staunch supporter of labor. This would be the first time among many that he’d take a stand for working people.

“My president had known him for a while, but that was my first time ever meeting Harold Washington. He did everything that he could possibly do to save those jobs, and he wound up saving over half of them. And from then on, we became friends. I had no idea he would ever wind up running for mayor of the city of Chicago!” Daylie said.

In 1979, Daylie was elected president of AFSCME Council 31. With 43,000 members across Illinois, Council 31 was the state’s largest public employee’s union. Soon, she’d be pulling out all the stops to help her friend become the first Black mayor of Chicago.

In 1983, Washington ran for mayor. Daylie was heavily involved. One of Washington’s key campaign promise was to give all city workers the right to collectively bargain. It would mean that thousands of soon-to-be AFSCME members working for the city would have the right to bargain for better pay and working conditions.

“Some workers could collectively bargain, some couldn’t back then. I represented housekeepers, clerks and janitors, workers like that. And since he promised he would give us collective bargaining, it was on. I think we were the first union that endorsed him,” Daylie said.

“Our headquarters were at the old packinghouse, which was not too far from the Robert Taylor Homes along State Street,” said Daylie. ” We did things like babysit so people could go out and vote. We’d take people to the polls. Anything that needed to happen to help people get out to vote. We went up into the projects and made sure people were taken care of so they could vote.”

Harold Washington was sworn in as mayor on April 29, 1983, and was reelected to a second term four years later. He would remain a close friend of Daylie’s until his death in 1987.

Harold Washington’s election had an impact that was life changing for many city workers. Throughout the second half of the 1980s, thousands of AFSCME members won raises upwards of ten percent over three years, more paid time off, and other benefits. Women and people of color who made up AFSCME now had the ability to collectively bargain.

Two decades later, Daylie would play a role in the ascent of another Chicago political dynamo: Barack Obama.

At the turn of the 20th century, Barack Obama was just beginning his ascent up the political ladder, vying to represent Illinois’ 13th district as State Senator.

“We had an organizing campaign at Resurrection Hospital at the time, and he came out to support us. Then he wound up being our keynote speaker at a CBTU convention a few years later before he was elected president,” Daylie said.

Daylie was thrilled to be part of such historic Chicago political careers. An astute observer, she learned a lot from her interactions with politicians on the rise.

“Obama was a deep thinker. He reminded me a bit of Nelson Mandela,” Daylie said.

On the Move in Africa

It was a family meeting of the utmost importance. Daylie’s four children had called this meeting to prevent their mother from making one of the biggest mistakes of her life–at least in their minds.

“Mom, you can’t go,” her children pleaded.

They were worried about her safety. And rightly so. In order to embark on her trip to South Africa, Daylie had to sign several waivers and disclaimers.

But the trip was no ordinary trip. Daylie had been working for more than five years to raise awareness and bring an end to apartheid. Now, she was being asked to spend weeks across the Atlantic working as a poll worker for the 1994 South African general election.

“We had a little chat and I explained to them that this was so important,” said Daylie. “I explained how it was important to stand up for freedom, and the right for everyone there to vote. It was personal to me.”

The trip was a culmination of Daylie’s work to end apartheid, which began in 1987. She co-chaired the newly formed Illinois Labor Network to End Apartheid. She led marches, meeting, boycotts and more. It was hard to find a more staunch supporter of ending apartheid in South Africa than Dayle.

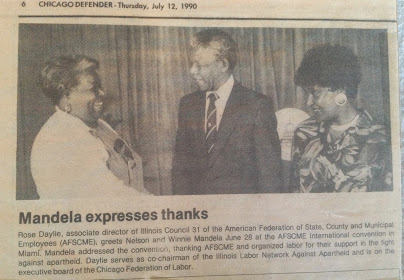

In 1990, Mandela was a guest at the AFSCME National Convention in Miami. Daylie met the freshly released from prison Mandela for the first time, along with his wife Winnie.

In 1993, the Illinois Labor Network to End Apartheid held a fundraiser for Mandela’s candidacy at Plumbers Local 130 union hall. Mandela received a hero’s welcome to Chicago. As the committee’s co-chair, Daylie proudly helped raise $60,000 for Mandela’s campaign.

“It was incredible. So, touching, to just look into his eyes after all he gave up for his cause. I wondered if I’d have the strength to do something like that, you know?” Daylie said.

The 1994 election marked the first in South African history where citizens of all races were allowed to vote. Millions waited in lines over four days in April to cast their ballot for one of six candidates for president. Nelson Mandela, previously held prisoner for over 20 years, was the leading candidate in the eyes of millions of newly enfranchised black and brown voters.

Daylie travelled to Johannesburg along with over 100 other delegates selected by their unions to participate. A few nights into her stay, Daylie recalled hearing a loud boom. She wrote it off as thunder. Moments later, she heard a knock at her door and was quickly ushered to safety. Someone had just bombed the African National Congress Headquarters up the street.

“And when we left for Cape Town. When we got there and turned on the TV in our hotel, we saw the airport we just left had been bombed,” Daylie said.

It would seem her children’s fears were realized, but Daylie was unfazed. In the days leading up to the election, Daylie traveled to hospitals and jails all over the region to allow people to cast their ballot. She expected the conditions in these places to be dark and scary. She didn’t expect to encounter so much racism and fear that in turn suppressed voters.

“There was a difference, a divide between Africans, and those with lighter skin and darker skin. A lot of Indian people had dark skin too. And so, you were treated better when you were colored. Many of the colored people got better jobs over there because of that. Some thought they’d lose their job if Nelson Mandela was elected,” Daylie said.

Once all the ballots were counted, Mandela was declared winner and Daylie joined in the celebration of a new dawn for South Africa. Unfortunately, she couldn’t stay and congratulate the newly elected president in person.

“It was so exciting when he won. I didn’t get to stay for the parties. But that’s OK, I had met him twice before,” Daylie said.

Claiming a Legend

The list of names Rose Daylie counts among her mentors reads like a who’s-who of the Black labor movement. Addie Wyatt. William Lucy. Charlie Hayes. They all nurtured her growth and opened doors for her, while actively building the movement. Daylie is among the trailblazing members of CLUW and CBTU, so much so, that each organization claims her as their own.

“There used to be an argument between Addie Wyatt and Charlie Hayes, well, not an argument, it was playful. They’d ask: Was I Black first or a woman first?” Daylie said.

Daylie had been a member of CLUW and CBTU practically since each organization’s inception in the 1970s. Her involvement in those organizations would propel her to run for office in her union at a time when representation at the upper levels of the labor movement was severely lacking. Daylie would both give and receive her greatest support from CLUW and CBTU.

In 1976, Daylie was elected president of AFSCME Local 1610. This meant new experiences and responsibilities, including coalition building and participating in statewide and regional organizations like the Illinois AFL-CIO. She remembers the stark reality she saw while attending her first statewide labor conference.

“The room was packed, but I only saw three, maybe four Black people. Bill Lucy, Addie Wyatt, and Elwood Flowers. I said to Addie, ‘Have you counted how many of us are here?’ She said, ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘I don’t think I’m going to last with this.’ She said, ‘What are you doing for lunch?’ And so, she explained to me over lunch that it was important to stick with it because there were so few of us. And I couldn’t walk away,” Daylie said.

Daylie believes her drive and passion led to her rise as one of the most respected leaders of Chicago’s labor movement. She became the first Black woman to serve on the Chicago Federation of Labor’s Executive Board in 1987 and was later elected First-Vice President of the CFL.

In 2023, the CFL renamed its annual women’s award, the Rosetta Daylie Woman of the Year Award. Awarded annually since 1982, Daylie was the 1990 recipient of the award that now bears her name.

“You know who one of the first people I call for advice is? Rose Daylie,” said CFL President Bob Reiter. “She is one of our strongest and smartest leaders in the Chicago labor movement. She’s the longest serving delegate on our board and our First Vice President. She embodies everything the award stands for. Her contributions to the labor movement, the black community and civil rights are innumerable.”

In addition to her role as First Vice President of the CFL, Daylie remains active with CBTU, Visionary Friends and other organizations. She’s traveled abroad and cherishes her time with her grandchildren.

Reflecting on her time in the labor movement, Daylie’s passion and drive every day came most often right from the members she was serving.

“It was about making sure the workers got better deals, making sure what they needed was taken care of. I never thought much about my sense of purpose. It was always right there in front of me,” Daylie said.

No wonder so many organizations try to claim her as her own. Rosetta Daylie is a living legend of the labor movement.